The Grande Dame Icon Of 1940’s Ski Wear Fashion

Colorado’s own Ann Bonfoey Taylor shows distinction, elegance and grace in fashion and to those around her

Model, ski apparel designer, and U.S. Ski Team member Ann Bonfoey Taylor poses for Town and Country magazine in November 1965. (Retrieved from the Library of Congress) | Photos courtesy of Toni Frissell

Grande dame. The phrase conjures women of distinction, elegance and grace. Women “of a certain age.” Women who are intelligent, accomplished, charming. Colorado’s own Ann Bonfoey Taylor had all of that, but what made her a truly grand grande dame has far more to do with the fabric of her being than any clothes she ever wore.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1910, Ann was raised in Quincy, Ill. There, her father had a little airstrip carved out of a cornfield where Ann learned to fly along with her brothers.

Ann attended boarding school in upstate New York. Shortly after graduation, she was encouraged to marry Princeton undergrad James Cooke, and produced two children in short succession. The couple relocated to Vermont, where Ann mothered her children while also modeling in New York City and maintaining a national tennis ranking that took her all the way to Wimbledon. Ever the athlete, she eventually took a fancy to the new sport of downhill skiing.

Teaching herself to ski, she progressed quickly. Her penchant for navigating a notoriously tricky run at Mount Mansfield in Vermont earned her the moniker “Nose Dive Annie,” and her talent and dedication was rewarded with a spot as an alternate on the 1940 U.S. Ski Team.

In December 1964, Bonfoey Taylor wore a flouncy skirt while skiing in Vail. (Retrieved from the Library of Congress)

Soon, however, the war dashed her competitive hopes, as the Olympic games were canceled. Shortly thereafter, she learned her husband was cheating on her with a teammate. They divorced, and she bravely faced the mountain of judgment familiar to single mothers of that era. “I then had to decide what on earth I was going to do with my life,” Ann recalled. She was very much alone, with an ex who had “no intention of taking care of me properly,” she said. Her family fortune had been misspent by her father and grandfather. “The only thing I knew a little bit about was aviation. I knew I liked planes.”

Determined to provide for her two young children, Ann sold a piece of jewelry to pay for flight lessons and enrolled as an aviation student at the University of Vermont in 1941. She earned her spot among an elite group of 25 women to hold commercial flight instructor licenses at the time, so was snapped up by the U.S. Army to train Air Corps cadets. For the next few years of the war, she would travel six days a week between a rented barn-cum-house in Stowe, Vt., where her children lived with a maid, and her training grounds at the Burlington Airport.

Even during wartime, Ann was a triumph in style. She earned her first full page in Harper’s Bazaar in 1943, posing next to an open-cockpit plane, her expression joyful and hopeful as she stands with seemingly adoring male students. Later, she would share that her road to becoming a pilot—a woman operating very much in a man’s world—was neither easy nor welcoming.

After the war ended, Ann’s interest in fashion led her to a new career as the first female to become a ski-wear designer in the U.S. Her eye-catching ski attire had already been turning heads, so she launched Ann Cooke Skiwear out of her barn. Ingeniously creative, Ann loved to use military and ethnic garb (a Scottish sporran as a statement-making fanny pack, or an Arabian head scarf acting as a balaclava); the single mother never failed to make a splash. Her bold visit to the office of Harper’s Bazaar editor Diana Vreeland, wool sweater samples in tow, resulted in the photo shoot of her dreams. In January 1946, Ann had six pages in the magazine, herself the cover star, wrapped in one of her own signature knits. Her designs graced mannequins from Saks Fifth Avenue to Bonwit Teller. The company was later sold to Lord & Taylor, proving that she had not only found editorial and critical success, but against all odds also attained commercial success.

Just when Ann’s business seemed to be peaking, into her boutique in Stowe, walked a tall and handsome Texas oilman, Vernon “Moose” Taylor, in search of a good pair of ski pants. “I thought he was delicious,” she would later gush. She surreptitiously gathered some girlfriends and followed him to Mont-Tremblant Ski Resort in Canada, orchestrating an “accidental” meeting. Little did she know the zipper of the pants that he purchased had failed at breakfast that morning. Moose admonished that they were the most appalling clothes he’d ever bought. Ann invited him to have a drink that evening.

After a whirlwind courtship, the two married. Ann closed her fashion business to move to Texas, but shortly thereafter the couple relocated to Denver, settling into their Burnham Hoyt-designed (Red Rocks Amphitheatre, Central Public Library) European manor to raise their brood, which soon included four more children. Ann was the resolute hostess, and much like her friends Nan Kempner and C.Z. Guest on the East Coast, she hosted royalty, dignitaries and social luminaries regularly at their Lakewood estate. Notably, England’s Prince Philip, Gerald Ford, Gregory Peck, Henry Kissinger and Truman Capote all dined around her table.

Ann became a serious equestrian at this time, employing a riding instructor to work with her five days a week. She and Moose rode daily and were not only members of the intrepid Arapahoe Hunt in Colorado but also hunted regularly in Virginia and England. As a late-blossoming rider, Ann impressively mastered the art of riding sidesaddle, but she was just as comfortable in a Western saddle on their Montana ranch.

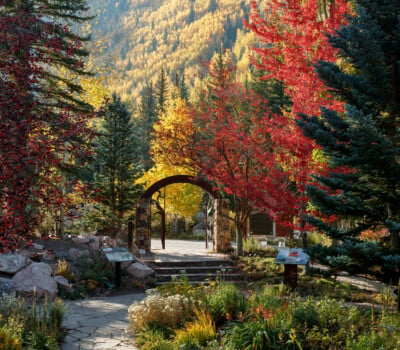

Soon, the sporty Colorado couple were heavily involved in the new ski town of Vail—investing money and a great deal of effort to put the town on the map. They erected a fabulous French manor at the base of Bear Tree Run. It quickly became the center of Vail society, with beguiling Ann at the helm.

It was then that Ann began to view fashion as a collector. She and Moose traveled yearly to Paris, where she developed deep and lasting relationships with the greatest designers of the era: Charles James, Cristobal Balenciaga, Madame Gres, James Galanos, Mariano Fortuny and Hubert de Givenchy. “Her closets were vast and immaculate,” says granddaughter Ashley Campbell Taylor. Her cedar-lined treasure troves housed the decade’s finest haute couture as well as equestrian, skiing and hunting attire that Ann designed with houses such as Hermes.

Always the fashion maven, Ann Bonfoey Taylor in a light blue gown, adorned with fur arm cuffs for Vogue magazine in May 1967. (Retrieved from the Library of Congress)

Ann, at age 55, became a media and fashion darling: In 1965, Life magazine ran a photo essay titled An Inventive Skier’s Worldly Wardrobe. In 1967, Harper’s Bazaar named her “One of the 100 Great Beauties of the World.” Vogue published a story on her “wit and dash,” and Town & Country printed “The 101 Hats of Mrs. Vernon Taylor.”

Ann’s attention-getting accessories—the Mongolian fur parkas produced in a rainbow of colors, military hats and paraphernalia galore—certainly turned heads. Although she didn’t shy from sartorial drama, a closer examination of her style reveals it to be very studied and refined. For day, often her clothing was restricted to a neutral color palette—grays, browns, navy blue, loden green. For evening, she collected sumptuous silk ball gowns, cocktail sets and chic pantsuits with dramatic overcoats. The tanned blonde favored jewel tones and intense colors for evening, but also sophisticated celadon, grayed lavender and robin’s-egg blue.

She was enamored with architecturally challenging pieces and the perfection of cutting and draping so masterfully exemplified in the work of her friends James and Madame Gres. She valued an exceptional cut and fit over any adornment or embellishment, says fashion curator Dennita Sewell and Ann’s daughter-in-law Michelle Taylor in Sewell’s book chronicling Ann’s fashion collection, Fashion Independent: The Original Style of Ann Bonfoey Taylor.

Ann also clearly loved a good set of dramatic eyelashes. She would never be caught in red nail polish or lipstick—pink was de rigueur. Her hair was always coiffed, and she had a love of statement jewelry, especially cuffs. She dressed for the occasion, and clearly had fun doing so.

She and Moose spent more than 60 years happily married, with their family and vast array of friends throughout the world, riding horses and skiing well into their golden years.

After her death at 97, 60 of Ann’s ensembles were gifted to the Phoenix Museum of Art. Art and Antiques Magazine named the donation one of the top 100 museum gifts of 2008. The ensuing exhibition of the collection, which also traveled to the Georgia Museum of Art, offered up Bonfoey Taylor as a true grand dame and one of the great style icons of our time.

Anna Jensen is an international journalist and stylist who grew up in Colorado. Coming from an equestrian family, most days she’s still horsing around with her young daughter. Follow along @annajensenfashionstylist on Instagram.